Use Word Clouds and Sentiment to Understand Text Comments

The first part of this series explains typical steps that a survey analyst takes to prepare free-text comments for Natural Language Processing (NLP). In this part, we describe four methods by which a cleaned and standardized corpus lets NLP reveal insights.

Create a Word Cloud of Common Words

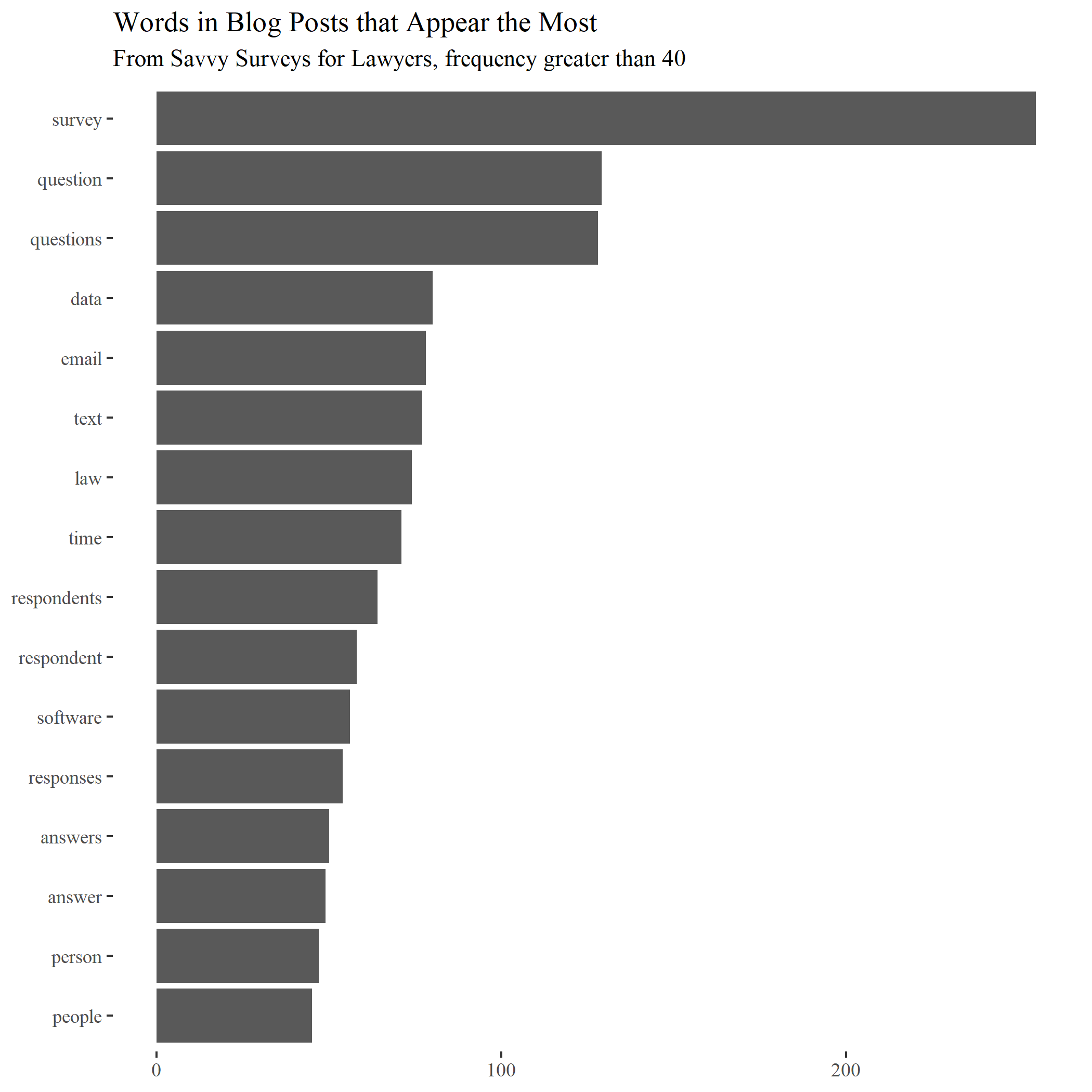

From the document-term matrix, software can total how many times each word appears in the corpus as a whole (all of the text questions combined text). A bar chart with the most frequent words can depict the totals. As in the bar chart below, which shows the frequently-used significant words in the first 25 posts from this blog, this simple effort makes clear the thrust of the writing. The word “survey” leads the way with almost 250 appearances. At the bottom end, “people” appears about 40 times. Note that the words have not been lemmatized.

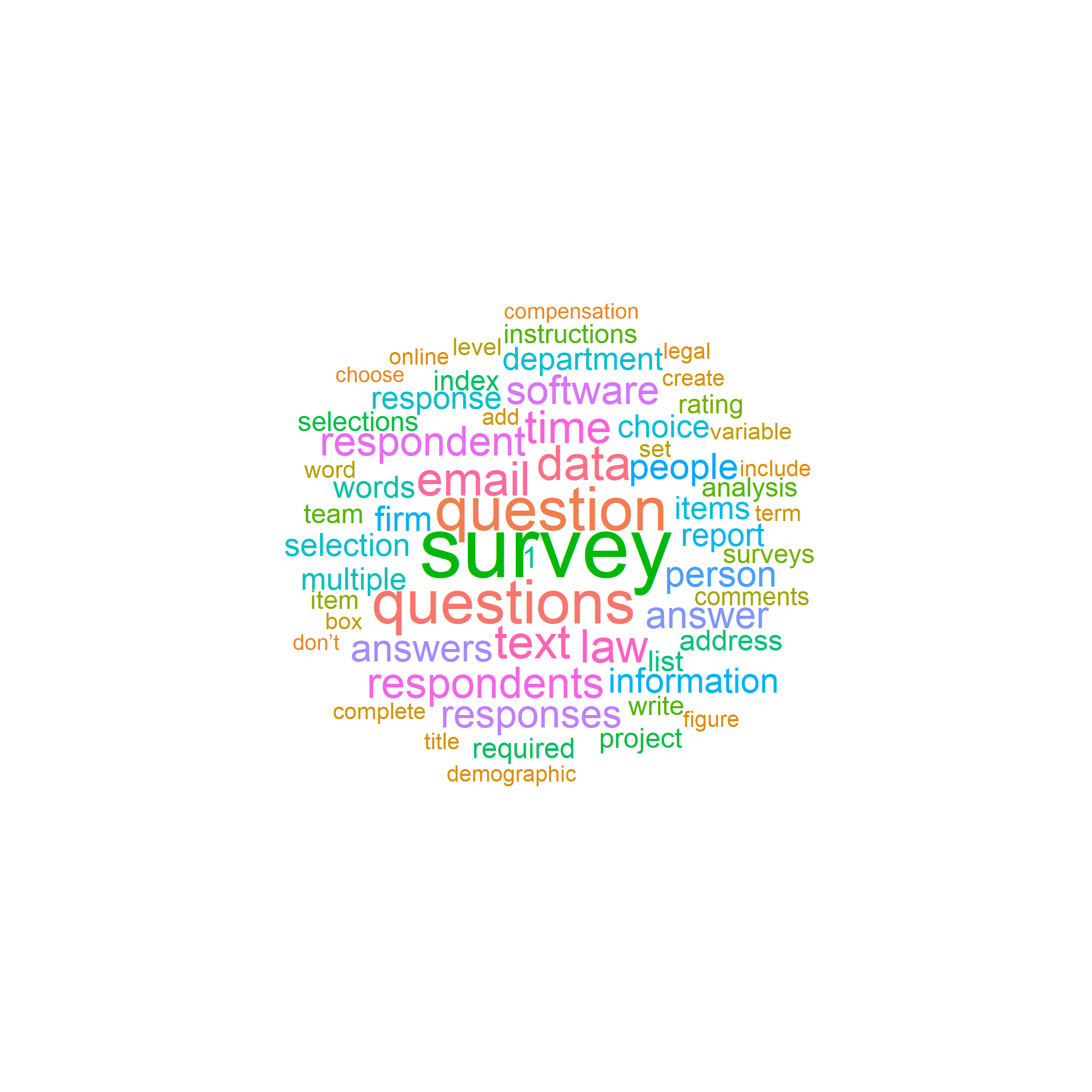

A more visually compelling way to convey a similar finding relies on a word cloud plot. Below is a word cloud of the seventy-five most frequent words used in the same blog. The location of a word in the cloud has no meaning, but the font size and color, which you can pick, corresponds to its relative frequency. Thus, “survey” and “question” appear most often.

The layout of the cloud varies each time you run the software, unless you set a seed to force the software to reproduce the layout each time. You can specify how many words to include and can even custom shape the “cloud.” I could create a question mark symbol, for example, and fill it with the word cloud words.

A person can spend much time refining the terms that form the word cloud. For example, “choose” should be in the supplemental stop-word list; “law” should be enjambed with “firm”; and it is not clear that “don’t” adds value. On the positive side, we can be sure that the major topic of the 2,928 unique terms in 25 posts is “surveys,” and much discussion centers around questions on those surveys. For a Bag-of-Words representation, a word cloud conveys many insights.

Determine the Sentiment of Comments

Another NLP method is “sentiment analysis,” a technique that addresses the emotional valence of text comments (positive, negative, neutral – or more nuanced descriptors). For example, a survey analyst might combine text comments to this question: “How much influence does our mission statement have on your day-to-day work?” Software can calculate the overall emotional valence of the words in the aggregate or by respondent. To do so, the analyst picks one or more lexicons of sentiment classification. In a recent project, I used one called “AFINN” that has scored 2,477 words on a range from -5 (very negative) to +5 (very positive).

As one example, “abandon” has an AFINN value of -2, somewhat negative, whereas “accomplish” and “competent” are both +2 terms. The sum of the sentiment scores makes up the overall score for a question. Thus, if all the comments to a question had twenty words from AFINN, which words have appeared more than once, the total scores of those words quantifies the positive or negative lean of those comments.

Other lexicons of word sentiments exist, e.g., “Bing” has 6,789 words tagged “positive” or “negative”; “NRC” tags 13,901 words with eight basic emotions (anger, fear, anticipation, trust, surprise, sadness, joy, and disgust); and “QDP” 3,732 words. The R package Syuzhet covers four lexicons (including “Stanford”) and makes available calculations for “emotional entropy” (variations in sentiment within a piece of text), trends over time (such as from early respondents to later respondents), and standardized measures across the four lexicons. You can apply supplement or modify the lexicons and can apply more than one to your comments to create an aggregate sentiment score.

A bar chart can display the comparative sentiment scores between text questions. Sentiment scores can also contribute to a synthetic index variable or to a categorical classification.

Findings regarding sentiment, however, would be skewed if some respondent wrote significantly longer comments. Their terms would unduly influence the average sentiment of the question. To put all the comments on the same footing, you can divide the sum of the sentiment scores for each response by the total number of sentiment words in the response. A normalizing step like this appears frequently in data analysis to convert numbers that vary significantly to a similar scale.

We close by noting that sentiment analysis paints with broad strokes. For example, a survey respondent might write, “Our mission statement is not wonderful.” A basic algorithm will score “wonderful” as strongly positive, yet the comment is critical and negative. Similarly, software cannot translate sarcasm (“We love being serfs in a medieval village!”) into credible sentiment. Another issue is how many words may have no sentiment value in a lexicon. Third, one can debate the sentiment rating of a word, such as whether “asset” is only a +2. Still, despite all the caveats, a directional conclusion is possible from free text regarding the strength and direction of respondents’ feelings.